by Michael Hofferber. Copyright © 1996. All rights reserved.

There is a story told by Idaho's Basque sheepherders about Basa Faun, a gigantic hairy ogre that resides in mountain caves and feeds on human flesh. A handful of salt in one's pocket will keep the beast away, they say, but one poor shepherd was careless and got caught unawares.

Basa Faun grabbed the trembling shepherd and said, "If you state three irrefutable facts I shall not feast on your flesh today."

Basa Faun grabbed the trembling shepherd and said, "If you state three irrefutable facts I shall not feast on your flesh today."The shepherd thought a moment, then told Basa Faun, "Some say that when the moon is full, night is as clear as day. That's not true.

"Some say corn bread is as good as wheat bread. But that's not true.

"I say, had I known you were going to be here I wouldn't have come. And that's true!"

Basa Faun kept his word and spared the shepherd, who never again left his sheepherder's wagon without salt in his pocket.

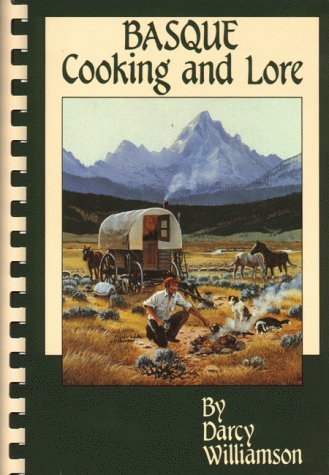

Idaho author Darcy Williamson included this story in her collection of recipes and stories, "Basque Cooking and Lore" (Caxton Press). A veteran cook with a half dozen cookbooks to her credit, she tested and refined all 107 recipes included in the Basque cookbook.

T

he meals prepared and the tall tales told by Basques in Idaho, Nevada and Oregon are not the same as those in Europe, Williamson explained. The environment of the Rockies, its food sources, and the experiences of Basque immigrants and their children in this country has changed the native culture. "Their recipes are founded on traditional dishes, but they are also uniquely different," Williamson noted.

he meals prepared and the tall tales told by Basques in Idaho, Nevada and Oregon are not the same as those in Europe, Williamson explained. The environment of the Rockies, its food sources, and the experiences of Basque immigrants and their children in this country has changed the native culture. "Their recipes are founded on traditional dishes, but they are also uniquely different," Williamson noted.Chukar and steelhead, for instance, are not found in the Basque homeland. But in the Rockies Basque-style chukar roasted with strips of bacon and garnished with grape leaves is based on old country poultry menus, and steelhead baked with onions and peppers is influenced by traditional seafood cuisine.

Dishes featured in the book include chick-pea and fresh mint soup, berza (cabbage with short ribs), blood sausages, chorizos, chimbos (small game birds with garlic and parsley sauce), boletus custard and tongue with wild mushroom sauce.

Though she is not Basque herself, Williamson grew up among Basques in McCall and was interested in the people and their culture. "Most of my recipes came from men," Williamson pointed out. "In the old country the men prided themselves on their culinary skills."

The Basque men were also more eager to share stories than were the women Williamson met. One acquaintance led to another as the author traveled throughout Oregon, Idaho and Nevada, and she kept a growing file of stories and recipes stashed away until she was ready to write her book.

One story she heard in Nevada told of a young man named Jose who immigrated from the Euzkadi region of northern Spain in the fall of 1922. A strict immigration quota had been set in 1921, but because of a labor shortage on sheep ranches Idaho and Nevada congressmen got special legislation approved making visas available to sheepherders.

Jose and Alejo, another Basque fresh from the Old Country, were instructed to trail a band of 750 sheep over a mountain range to winter pasture. On the second day of their journey they woke to find their camp blanketed with snow and not a sheep in sight.

"Where are the sheep?" shouted Jose.

"You tell me! You're the sheepherder!" Alejo shouted back.

"Not I," said Jose. "I'm a fisherman."

"And I am an innkeeper," Alejo said.

After staring at each other in disbelief, the pair went off in search of the missing flock, which they found winding its way down the mountain towards winter pasture.

The Basque people, according to Williamson, are generally down-to-earth and conservative. Like Jose and Alejo, their interests and occupations extended far beyond sheepherding. Basque cookery, like the people, is hearty, straightforward and moderately spiced.

Williamson's personal favorite among the dishes profiled in "Basque Cooking and Lore" is Basque-style paella. The paella is made with baked chicken, shrimp, clams, and green olives. These ingredients are cooked in a chicken broth with garlic, onion, green peppers, tomatoes and rice, and seasoned with coriander, salt, pepper and a sprinkle of sherry.