by Michael Hofferber. Copyright © 2002. All rights reserved.

From up above, the truth can seem so obvious. Satellite photographs of Earth taken from space show us where storm systems are located and in what direction they are headed. These images can tell us how thick the clouds are, their temperature and movements, and suggest a likelihood of precipitation.

But an image is not reality. Those white shapes on the satellite image could be snow, ice, fog or maybe just clouds. Down on the surface there could be a blizzard, a gentle rain or overcast skies.

But an image is not reality. Those white shapes on the satellite image could be snow, ice, fog or maybe just clouds. Down on the surface there could be a blizzard, a gentle rain or overcast skies.The process of verifying what a satellite or remote sensing image really represents is called "ground truthing." It takes ground truthing -- going to an area to take field measurments or communicating with someone on location -- to find out what's really happening on the surface.

Ground truthing is essential to determining the accuracy of overhead imagery of all kinds, from weather satellites to remote-sensing crop data to military intelligence. Without it, meteorologists will err, crop inputs will be misapplied and missiles will fall on unintended targets.

From up above, the wheat and barley fields of southern England appear to have been visited by extraterrestials. Flying overhead, you can spot dozens of geometric shapes, lines and pictograms carved out of the croplands below -- designs that surely must have been made from the air, where the artist could see what he was doing.

These "crop circles," which began appearing each summer in the 1970s, have become a tourist attraction in England, as thousands of people flock to the fields to gawk and ponder their significance.

Are they the work of aliens from outer space? Pranksters? Unusual microbursts of wind? Or is there something supernatural going on in the land of Merlin and Stonehenge?

Down on the surface, there are explanations aplenty. One group of landscape artists, calling itself The Circlemakers, claims responsibility for many of England's "crop formations." They sneak off into fields at night with schematics in hand, carefully flattening crops (bending but not breaking stalks) into elaborate designs. They've even begun taking consignments for commercial projects.

Like corn mazes in America, crop circles in England provide farmers who have them a supplemental source of income.

There are others taking the crop circle phenomenon more seriously, though, accusing The Circlemakers and others of being mere graffiti artists and imitating the work of aliens or something supernatural. Cerealogists, those who study crop circles as a science, have carefully scoured crop formations and found stunted seed-heads, enlarged and bent nodes, deformed and stunted seeds, and growth reduction in seedlings within their boundaries.

According to the Des Moines Register, Michigan biophysicist William C. Levengood has found tiny, nearly pure spheres of iron in the soil where crop circles occur. He theorizes that a magnetic field draws particles in, heats them to a molten state and disperses them in a rotating fashion inside the crop formation.

Although they look stunningly supernatural from the air and seem impossible to create from the ground where an overhead perspective is not available, crop circles are well within the creative limits of a prankish undergraduate student.

Writing in Scientific American, Matt Ridley describes how he created a crop circle with his brother-in-law late one August night a few years ago:

"I stepped into a field of nearly ripe wheat in northern England, anchored a rope into the ground with a spike and began walking in a circle with the rope held near the ground. It did not work very well: the rope rode up over the plants. But with a bit of help from our feet to hold down the rope, we soon had a respectable circle of flattened wheat.

"Two days later there was an excited call to the authorities from the local farmer. I had fooled my first victim."

The same methods were used to create the circles in the motion picture Signs on 200 acres of rented farmland in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In the movie, actor Mel Gibson portrays a farmer who finds an elaborate crop formation in his field.

Ridley admits to making two more crop circles using improved techniques -- a garden roller filled with water and planks suspended from two ropes.

"Getting into the field without leaving traces is a lot easier than is usually claimed. In dry weather, and if you step carefully, you can leave no footprints or tracks at all... One group of circle makers uses two tall bar stools, jumping from one to another."

Like the clouds on satellite imagery, the shapes above do not reflect the truth below. Crop circles are not everywhere the same -- the ones found in America, New Zealand, Canada and elsewhere obviously have different origins. Their truth is not universal, but personal and allegoric, and rarely grounded in reality.

Rural Delivery

Ground Truthing Crop Circles

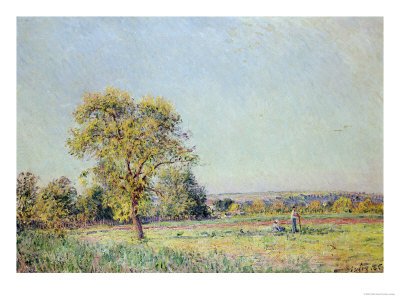

Artwork: Aerial View of Crop Circles in a Wheat Field